The Museum.

A roundup of museum visits to inspire your next culture trip, from obscure open houses to the Louvre.

Demands for the repatriation of cultural objects have snowballed over the past decade, with major institutions facing mounting public pressure to return works to their former owners or place of origin. Greece, for example, is so determined to get the Parthenon Marbles back from the British Museum that it built a new museum of its own at the base of the Acropolis, ready to take the sculptures when they finally make their way back to Attica. Maria Altman’s quest to reclaim Gustav Klimt’s portrait of her aunt—stolen by the Nazis and given to the Belvedere Museum in Vienna—was so captivating a story, Hollywood made a movie starring Helen Mirren.

Allegory of Arithmetic (1557) by Frans Floris, Louvre Abu Dhabi (right).

When museums aren’t hoarding loot they have the power to do great things for the world, shining light on cultural exchange and fostering mutual understanding and cooperation between peoples. They can also be places of great emotion: even without the full suite of Parthenon Marbles, the Acropolis Museum stands as not only one of the most ravishing museums on the planet, but a beacon of Greek pride and resilience.

Waterfall in the Glen (1927) by Winston MacQuoid and Ben Nicholson’s Porta – San Gimignano (1953) at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge (left); Hercules the Archer (1910) by Antoine Bourdelle in the Great Hall of Musée Bourdelle, Paris (below).

Even without the Acropolis Museum, Athens is home to an extraordinary lineup of modern-day culture temples—and relatively unique in Europe as two things never occurred there. The Italian Renaissance never made it to the Balkans, an outpost of the Byzantine and Ottoman empires at the time. And unlike much of the continent, Greece never had a noble class to support the arts. Instead, its cultural flourishing has been a stop-start affair since it gained independence from the Turks in 1832, with a stratum of wealthy Greeks making massive contributions to the fledgling nation’s cultural scene. Favourites include the Benaki Museum (1930), home to thousands of years of Greek creativity, from ancient sculpture to a stellar display of costumes; the otherworldly Cycladic Museum (1986); and the Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation (2019), with its three-billion-dollar collection of modern art.

The Erechtheion Caryatids (421-405 BCE), Acropolis Museum, Athens (right); Ömer Uluç’s 3 Men, 4 Women, Visitors (1989) at Istanbul Modern; the Capitoline Sappho (Roman copy of 5th-century BC Greek original), Capitoline Museums, Rome (below).

Further east in Nepal, Patan Museum is home to architectural relics and religious works, such as a 9th-century image of Indra—the Hindu Zeus—and a magnificent 12th-century Shakyamuni Buddha seated in meditation. All pieces in the collection have one thing in common: they were stolen. When the Himalayan country opened up to the world in the 1950’s, the Kathmandu Valley was an open, living museum. An illicit trade in religious art followed, stripping Nepal’s gods from their shrines. The treasures on display at Patan Museum are items that were either abandoned by thieves or intercepted before they could leave the country, making the criminal world the museum’s largest benefactor.

There are also happy moments of cultural repatriation. While I was in Nepal, the Art Gallery of New South Wales returned an 800-year-old strut that had been stolen from a temple in Patan in 1975.

Detail of a four-faced Shivalinga (17-18th century), Patan Museum, Nepal (left).

The museum itself is a jewel of Newar architecture—a 17th-century royal compound in slim red brick, intricately carved timber and golden doors and windows overlooking Patan Durbar Square. Patan is the oldest of three ancient capitals of the Kathmandu Valley, the others being Kathmandu and Bhaktapur. This trio of city states was ruled for more than half a millennium by the Malla dynasty—cousin kings and cultural rivals whose ancestors fled the Muslim Conquest of India and came to power in the Valley around 1200 CE. Armed with taste and money (the valley lay at the crossroads of lucrative trade routes), their reign ushered in a golden age similar to the Italian Renaissance. Falling into disrepair after the Malla kings were overthrown in 1769, the palace was restored in the late 20th century by Austrian conservation architect, Götz Hagmüller, ready to take the the refugee art. It’s simple but sophisticated, with understated museum labels and ultra low lighting, recreating the candlelit, incense-filled atmosphere of the Malla kings centuries before.

The back of a monumental painting by Guercino at the Capitoline Museums, Rome (right); Palazzo Doria Pamphilj, Rome; a detail of Caravaggio’s John the Baptist (1507-10), Galleria Doria Pamphilj (below).

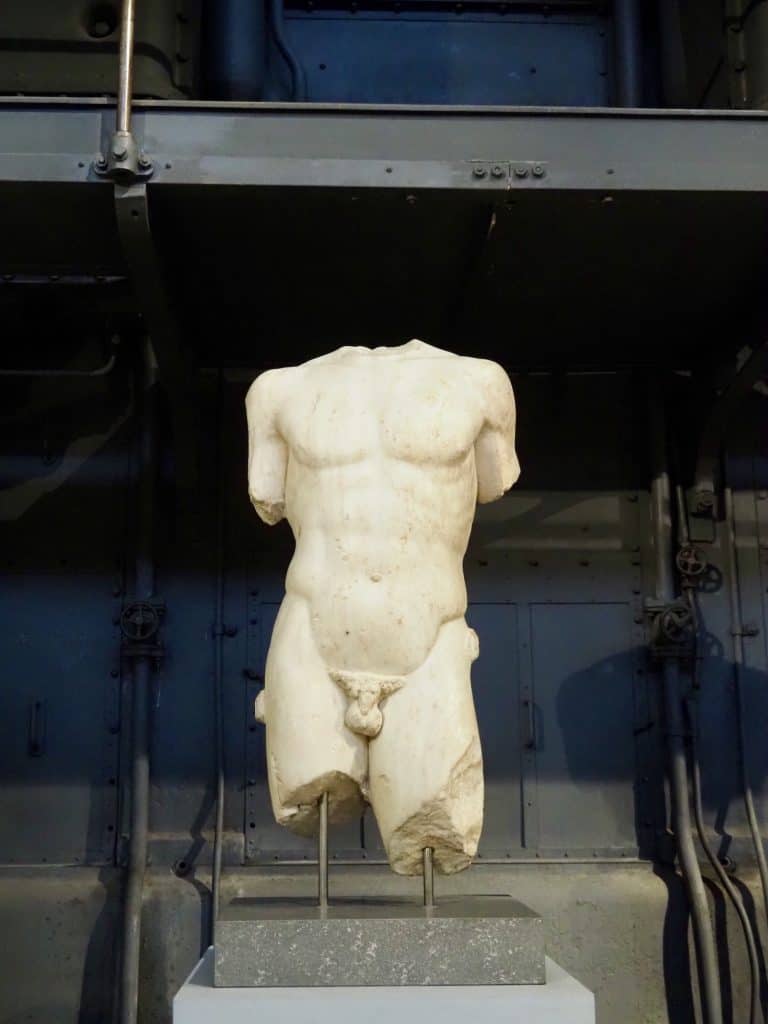

The oldest surviving museums are the Capitoline Museums in Rome, a cluster of art and archaeological museums in Piazza Campidoglio, at the top of the Capitoline Hill. The museums came into being when Pope Sixtus IV donated a collection of important ancient bronzes to the people of Rome in 1471. Since then it has grown to include mediaeval and Renaissance art, jewels and a couple of Caravaggios. Across town, the early 20th-century power station, Centrale Montemartini, is home to the Capitoline Museums’ vast surplus of ancient sculpture. Antinous, Apollo and other marble beauties are juxtaposed against the industrial framework of spaces such as the Hall of the Machines, a sanctuary of contrasts devoid of the city’s ubiquitous tourist hoards.

Torso of Apollo (1st century CE), Centrale Montemartini, Rome (left); French sculptor Anotine Bourdelle’s studio, Musée Bourdelle, Paris; Hall of the Horatii and Curiatii, Capitoline Museums, Rome; courtyard of the Palazzo dei Conservatori, Capitoline Museums (below).

I love the democracy of museums and the opportunities they present, allowing us to reflect upon not just art but life itself.

Another semi-hidden gem on Rome’s saturated tourist trail is Palazzo Altemps, a Renaissance palace built in 1477 by Girolamo Riario (Sixtus IV’s nephew) and purchased by Marco Sittico Altemps (cardinal and nephew of Pius IV) a century later. Unfortunately, most of the connoisseur cardinal’s collection was sold off by his heirs over subsequent centuries and the palace fell into disrepair, granted to the Italian state in 1982. Serendipitously, though, this palazzo missing its collection was brought back to life when the contents of Villa Ludovisi, homeless since the villa was demolished at the end of the 19th century, were moved to Altemps.

Through careful examination of the Altemps archives, the museum-to-be was able to position similar figures and subjects from the Ludovisi collection in a way that recreates the layout as it had been at the time of the cardinal. Rather than presenting itself as an archaeological museum, Altemps has an air of carefree elegance, recreating the ambiance of a 16th-century private gallery.

The Doria Pamphilj is another favourite, a thousand-room palazzo on Via del Corso dripping in faded grandeur and the most valuable collection of Italian art still in private hands. Walls of the Galleria Doria Pamphilj (the open-to-the-public part of the palace) are hung frame to frame with works by Caravaggio, Tintoretto, Rubens, Brueghel, Poisson, Raphael, Bernini and the Caracci. A who’s who of Italian and European art, including Velasquez’s portrait of the family pope, Innocent X.

Kettle’s Yard was the creation of Jim and Helen Ede, who, in 1956, took a row of dilapidated workers’ cottages in Cambridge and crafted what is today one of the greatest pilgrimage sites for British Modern. The relationship between the house and the collection—think Christopher Wood, Ben Nicholson, Miró, Brancusi and Henry Moore, amassed while Ede was a curator at the Tate in the 1920s and 30s—is extraordinary. Showstopping works, each worth a small fortune, are hung low to be admired from armchairs and sofas, some of which are simply mattresses on the floor covered in Indian dhurries. Arrangements of stones found on the beach hold joint centre stage—as valuable to Ede as his trove of pictures. He opened the doors of Kettle’s Yard every afternoon during term for a cup of tea and a tour of the collection—there was even a loan programme where students could borrow art to hang in their rooms—and gave the property and collection to Cambridge University after he and Helen moved to Edinburgh in the early 1970’s.

Different in spirit but equally compelling is the Musée Nissim de Camondo in Paris. The haunting home of the French banker, Moïse de Camondo, the mansion was built between 1911 and 1914 and modelled on the Petit Trianon at Versailles. Brimming with French 18th century—including paintings by Élisabeth Vigée Lebrun and furniture that once belonged to Marie Antoinette—it was bequeathed to Musée des Arts Décoratifs upon Moïse’s death in memory of son, Nissim de Camondo, who died fighting for France in WWI. A plaque at the property also commemorates his daughter, Béatrice de Camondo, who died with her husband and children at Auschwitz.

I’ll plan travel around a great museum, as I did on my recent trip to Istanbul—story coming soon—stopping off in Abu Dhabi just to see the Louvre. Excited to see Jean Nouvelle’s UFO of a building, it was in the end the collection that blew my mind, a concise but wonderfully curated overview of man’s artistic achievement, from prehistory to the Khmer Empire and Cy Twombly. Objects from similar eras but different geographies are grouped together, highlighting the commonalities of human experience—a spirit much needed across the globe. As an art lover, dreamer and solo traveller, museum visits such as these are central to my own experience—the democracy and the opportunities they present, allowing us to reflect upon not just art but life itself.

Photography: Jason Mowen.

The Taragaon Museum in Kathmandu, Nepal; detail of the Juno Ludovisi (1st century CE) at Palazzo Altemps, Rome; the loggia, Palazzo Altemps (above); the Musée Nissim de Camondo, Paris (right); works by French sculptor Anotine Bourdelle at his studio, Musée Bourdelle, Paris (below).