Palaces of Rome.

Wealth. Intrigue. Lust. Betrayal. Beauty. When it comes to rich historical narrative, no city on the planet delivers quite like Rome.

From its mythical inception when the she-wolf-suckled twins, Romulus and Remus, fought it out to see who would found the city in 753 BC – Romulus won by the way and murdered his brother, otherwise the Italian capital would be Reme – a 2800-year-long soap opera so bloodied and dramatic has unfolded on the banks of the Tiber. Did you know, for example, that during the reign of Augustus, toward the end of the 1st-century BC, the city’s inhabitants numbered well over one million? Fast-forward to the 16th century, though, and Rome was a ghost town. Easy prey when the semi-mutinous troops of the Habsburg king, Charles V enacted their bloodthirsty Sack of Rome in 1527, leaving only 10,000 wretched Romans alive in the aftermath. Survival, however, is in the city’s phoenix-like DNA. Rome may have been down but as history has shown, it was never going to be out.

As centuries rolled by, the Rome of Michelangelo – who completed the ceiling frescoes of the Sistine Chapel just 15 years prior to the Sack – gave way to the Rome of Bernini and so on and so forth through Caravaggio, Canova, Garibaldi, Mussolini and Fellini. And now we have 21st-century Rome, an altogether different beast. Invading hoards are armed with selfie-sticks rather than swords as they box-tick their way between the Vatican, Colosseum and the Trevi Fountain. Step, however, just a few metres from this well-trod path and you’re sure to encounter more hidden Roman delights. The city’s residential palaces, of which there is a breathtaking plethora, hail from the Renaissance, Baroque and beyond, although their foundations are often ancient. Together, this amalgam of palazzi – perhaps the most exuberant of its kind, anywhere in the world – tells a good and emotionally charged chunk of the story of Rome.

PALAZZO FARNESE

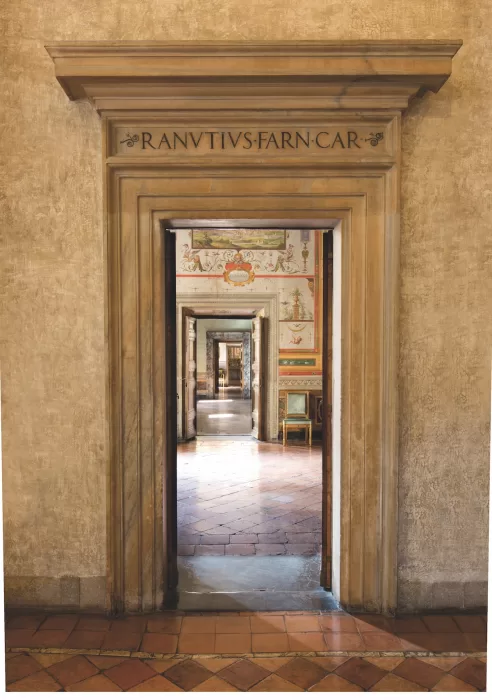

A peek inside Palazzo Farnese, the French embassy since 1874, was, until recently, nigh on impossible – a frustrating thing as it is without doubt the jewel in the crown of Renaissance palaces. The art critic, Robert Hughes, went as far as describing it as “the most sumptuous palazzo in Italy,” and having wandered its mighty halls, staterooms and courtyards not too long ago, I found myself in full and enthusiastic agreement.

The palazzo was the combined work of four architects, including Antonio da Sangallo the Younger and Michelangelo, but the protagonist in this tale is Alessandro Farnese, who was appointed cardinal at the behest of his sister, Giulia, then mistress to the infamous Borgia pope, Alexander VI. Known for his princely lifestyle, not to mention four illegitimate children and, as Hughes puts it, “an unknown number of by-blows,” the cardinal ordered construction of the palace in 1513. However the original plans were significantly expanded upon, in both scale and grandeur, when Farnese was himself elected Pope Paul III in 1534. He didn’t live to see the palace in all its finished glory, although he founded one of the first great collections of Greco-Roman sculpture – routinely uncovered in Roman lands and much desired at the time – to fill it.

The facade overlooks the somewhat tranquil Piazza Farnese – a surprise considering its close proximity to the hustle and bustle of Campo de Fiori. For any lovers of Michelangelo unable to face the claustrophobic conditions of the Sistine, one of the artist’s other ‘crowning’ achievements is the weighty cornice he created to to top the facade. The interior is a procession of architectural and decorative delights, beginning with the vestibule, where ticketed visitors are momentarily corralled between rows of magnificent 3rd-century granite columns that were stripped from the Baths of Caracalla, during the embassy’s lengthy security check. Even more breathtaking is the piano nobile, with its monumentally scaled Salon of Hercules, although all splendour is surpassed by the cycle of frescoes by the brothers from Bologna, Anibale and Agostino Caracci, in the Galleria Farnese (1597-1608). With the ‘Triumph of Love’ as its theme, the frescoes are as pagan and sexually charged as art at the time could be.

The palace and its contents formed part of the large dowry of Elisabeth Farnese (1692-1766), last of the Farnese line, when she married the Spanish Bourbon king, Philip V, in 1714. Their son then became King Charles VI of Naples and the Two Sicilies a territory in (and occasionally out of) Bourbon control over the years; and then his son, Ferdinand IV had the collection sent south. As a result, the National Archaeological Museum of Naples now contains what is arguably the finest collection of Roman sculpture on the planet. Francis II – the last king of the Two Sicilies – allowed France to establish their embassy in the palazzo, after the unification of Italy in the mid-19thcentury.

PALAZZO COLONNA

Alongside the Forum, Colosseum and Spanish Steps, one of then lesser-known landmarks chosen by William Wyler as backdrop for his 1953 film, Roman Holiday was the Galleria Colonna, contained within the palazzo of the same name. The opulence of the galleria, or great hall – an exuberant, 73 metre long triumph of Baroque art and architecture – provides the perfect stage for the film’s final scene, a press conference in which Princess Ann (played by Audrey Hepburn) forsakes love (Gregory Peck) for royal duty. Seven decades later, the palace remains one of Rome’s veritable, albeit lesser-known, treasures.

Home to the Colonna family, one of the oldest of the Roman aristocracy, Palazzo Colonna is about as close as it gets to a ‘royal’ palace in Rome. A vast architectural complex, begun in the 13th century on the site of an ancient Roman temple at the foot of the Quirinal Hill, the palazzo is often compared to Versailles. And with good reason: alongside endless enfilades of rooms and gorgeous gardens, the Galleria Colonna rivals the most finely gilded efforts of Louis XIV – a fitting home for Marie Mancini, the Sun King’s first great love who, eventually banished from the French court, was married to Lorenzo Onofrio Colonna in 1661.

Prince Lorenzo began construction of the gallery in the same year, a grand podium from which to flaunt the family cachet. Designed by Antonio del Grande and, amongst others, Bernini, it would take four decades to complete – the resplendent heart of a much larger renovation undertaken by the Colonna to transform what was effectively a medieval fortress into a luxurious palace throughout the 17th century. The art collection adorning the walls of the palazzo, including those of Galleria Colonna, is mind-blowing in scale and calibre. Of particular note is Annibale Carracchi’s seminal work, The Bean Eater (c.1583), in the Hall of the Apotheosis of Martin V – aka Oddone Colonna, who was elected pope in 1442.

A series of nudes, three by Domenico Ghirlandaio and one by Bronzino in the Hall of the Battle Column, which adjoins the Galleria Colonna, is an image that has remained with me since my visit. Recently restored, the four paintings gleam in what is an already lustrous space. They’re lascivious – so much so that clothes were later painted over the nubile flesh of Bronzino’s Venus, removed in the recent restoration. But what struck me was the monumental task of restoring, and maintaining a palace full of paintings, not to mention the palace itself. With no less than 31 generations of experience, though, it seems Palazzo Colonna and its contents are in good hands.

PALAZZO DORIA PAMPHILJ

Palazzo Doria Pamphilj is Visconti-like faded grandeur on steroids. Anyone who has seen The Leopard (1963), the filmmaker’s masterpiece, will have an idea of what I’m talking about. The contents, though, of this thousand-room palazzo are anything but faded. Adorning almost every inch of wall space in the Galleria Doria Pamphilj is a medley of paintings that forms the nucleus of one of the richest Italian art collections still in private hands. It contains a staggering quantity of Old Masters, from Bellini to Bronzino, Caravaggio, Tinteretto, Rubens, Brueghel, Poussin and the Carracci, not to mention Velasquez’s instantly recognisable portrait of the family pope, Innocent X. The procession of rooms open to the public, many of which also feature superb Roman-Baroque furniture, culminates, crescendo-like, in the magnificent Galleria degli Specchi, with its frescoes by Aureliano Milani depicting the labours of Hercules.

The palazzo’s story begins in 1489, when a Cardinal Santoro bought the site, a ruined former monastery, and began to erect a magnificent residence. Unfortunately it was a little too magnificent: Pope Julius II remarked that Santoro’s rich new digs were “more worthy of a duke than a cardinal” and just like that, Santoro was obliged to gift the property to the pope’s nephew, the Duke della Rovere. It was later bought by the Aldobrandolini family and formed part of the dowry of Donna Olimpia Aldobrandolini (niece of Pope Clement VIII) when she married Prince Camillo Pamphilj in 1647. Their daughter, Anna, married Giovanni Andrea III Doria, the union leading to the palazzo’s name.

Significant works throughout the 18th century saw the palace complex further expanded and embellished, including the enclosing of the second order of Santoro’s porticoes to create the Galleria, and Gabriele Valvassori’s elegant new façade (1731-34) that, even blackened by the fumes of the Via del Corso, is one of the most eloquent expressions of the Rococo in Rome.

Today’s patriarch, Prince Jonathan Doria Pamphilj occupies a mere ten rooms within the palazzo, with his Brazilian partner, Elson Edeno Braga and their two children. His sister, Princess Gesine, lives in another wing with her family, but they have little to do with each other since the princess challenged the status of her brother’s children (produced by surrogate) as heirs to the estate. It is ironic, as both the prince and princess were adopted from a London orphanage – but with almost a thousand rooms to separate them, they are unlikely to be in each other’s way.

PALAZZO ALTEMPS

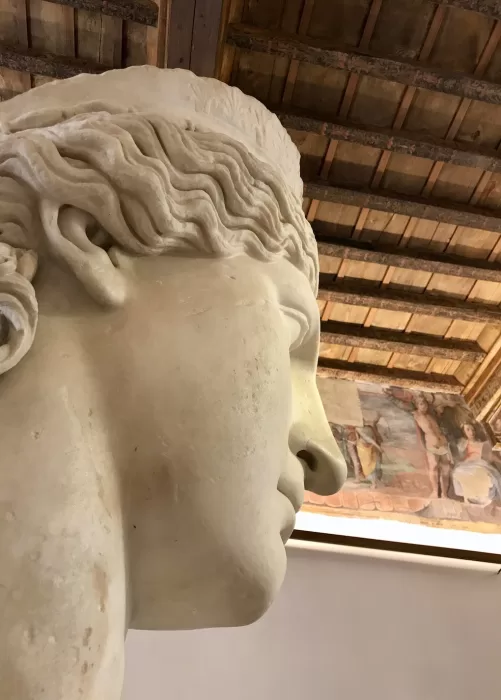

Palazzo Altemps was converted to a branch of the Museo Nazionale Romano in 1997 and now houses a good chunk of the museum’s collection of ancient sculpture. Its air remains one of carefree elegance: rather than presenting as an archaeological museum, in its current form it re-creates the ambiance of a 16th-century private gallery. It is an atmosphere quietly amplified by the fact that, for Rome, Altemps is decidedly un-crowded. Go there on the right day and much like the noble and ecclesiastical elite of times past, you’re likely to have the place all to yourself.

The palazzo dates back to 1477, when Girolamo Riario, a nephew of the della Rovere pope, Sixtus IV, began its construction. One of Riario’s claims to infamy was his involvement in the Pazzi Conspiracy to overthrow the Medici in Florence, leading to his assassination in 1488. The prevailing architectural form, however, derives from Marco Sittico Altemps, a cardinal and nephew of Pope Pius IV, who purchased the property in 1568 to house his extensive collection of books and sculpture. It remained in the Altemps family until the late 19th century when it became the property of the Holy See, and falling into a state of disrepair, was granted to the Italian state in 1982.

Most of the connoisseur cardinal’s sculpture was sold off by his heirs and now forms a part of the national collections of France, Denmark and Russia. Serendipitously, though, this palazzo-missing-its-collection was reinvigorated by a collection-missing-its-palazzo. Effectively homeless were the sublime contents of Villa Ludovisi, since they were purchased by the state after the villa was demolished in the late 19th century. Through careful examination of the Altemps archives, the new museum-to-be was able to position similar figures and subjects from the Ludovisi collection – highlights include the 5th-century BC Ludovisi Throne – in a way that recreates the cardinal’s original layout.

The palazzo’s richly decorated loggia is one of my favourite spots to pause in the entire city, where frescoes of pergolas and climbing plants are punctuated by busts of The Twelve Caesars. Altemps’ own set of Caesars – a staple of every self-respecting Renaissance collection – had long since been dispersed but during the 1990’s renovation, two of the original pedestals were found when the derelict loggia was being cleared. It’s from these two pedestals, alongside ten elegant copies, that the fabulous Ludovisi Caesars now stand guard over their new home.

VILLA ALBANI TORLONIA

Villa Albani Torlonia was a more recent addition to the scene. The name derives from Cardinal Alessandro Albani, for whom the villa was built between 1747 and 1763, and the Torlonia family, financiers to the Vatican, who purchased the villa and its contents in 1866. For lovers of Neoclassicism it’s an especially exciting addition. Although largely unheard of, even amongst Romans, this pavilion-like wonder is home to the world’s greatest private collection of classical art – the cardinal was an insatiable collector – and is considered to be the very birthplace of neoclassical taste. If we don’t include the heyday of the 18th-century Grand Tour, when the cardinal welcomed visiting aristocratic Brits and Germans to marvel at the sight of his collection, then this is the first time the villa has been open to the public, under the patronage of the recently established Fondazione Torlonia.

Albani purchased several plots of land just outside the Aurelian walls, not far from Villa Borghese, and consolidated them into an open, Italian-style garden, punctuated by fountains and follies such as the Temple of Diana, the ‘ruined’ tempietto and the Kaffeehaus. Architect, Carlo Marchionni designed the main building, the casino nobile, to preside over this dazzling and verdant mini-world. Despite its broad, two-storey façade, rising above a ground floor loggia, the structure contains only one bedroom as the cardinal usually retired to sleep at his nearby palazzo. More an architectural dream of classicism than an actual residence, ultimately its purpose was to house the collection.

With every wall, niche and shelf packed with antiquities, it’s easy to see how the tastes of English architect, Sir John Soane, were formed by his acquaintance with Albani. By the time Soane met the cardinal during his own tour of the Italian peninsula, the latter could hardly walk and was blind as a bat. But there was his exceptional and beautifully showcased collection begging to be imitated – something he would do later in his life in what is now his eponymous London museum.

A large fresco of Parnassus by Anton Raphaël Mengs in the villa’s main gallery created a sensation when it was completed in 1761, becoming a manifesto, of sorts, for the nascent neoclassical style. The star of the collection, though, is the marble relief of Hadrian’s lover Antinous, a kind-of Roman James Dean who drowned in the Nile in 130 AD and has been worshipped for his youth and beauty ever since. It was excavated in almost perfect condition from the private apartments of Hadrian’s villa in Tivoli in 1735. German art historian, Johann Wincklemann – another hero of Neoclassicism who served as the cardinal’s librarian and advisor from 1759 – described the relief as, “The glory and crown of the art of this period and of all periods.” Albani had the piece installed above a Rococo fireplace in one of the casino’s principle salons, where it rests today.

Jason will be hosting a small-group expedition from Rome to Salento in September 2024, exploring the palaces between long lunches, walks and aperitivi. Dates will be announced shortly.

From a story originally published in WISH.