Spiritual Awakening.

Dawn is magic hour in Nepal, when both Hindus and Buddhists perform puja, or worship.

This dawn, though, is special. It is my second day in Patan and I’m on a mission to see the annual chariot festival of the rain god, Rato Machindranath. I follow women in a rainbow of saris and men wearing the Dhaka topi, the pointed national cap, alongside denim-clad teenagers and throngs of children, one marking my forehead with the first of many tikas as the top of the chariot comes into view.

Capped with a 20-metre spire dressed in tree branches, garlands and flags, tethered temporarily by rope to surrounding buildings, the chariot has four enormous wooden wheels painted with eye motifs. Someone in the crowd tells me it is built from scratch every year by a sect of the Newar community, the historical inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley, to please the rain god and ensure good harvests before the monsoon. “What’s amazing,” he says, “is that it’s constructed without the use of a single nail.” I don’t doubt him. It looks like a half-cut tree about to fall.

Most people think it’s crazy, taking eight weeks to explore the culture of Nepal. Why would anyone travel to Nepal for anything but trekking, and how could I possibly need eight weeks? And why wasn’t I going to Bhutan instead, with its national happiness index and Aman resorts? But from the moment I arrive, standing between two temples in Swotha Square at 3am, I know I’m on the right path. With a three-tiered pagoda bejewelled in wind chimes on one side and a Mughal-looking shrine in carved stone on the other, it is as if I’ve passed through a portal and into another world.

As the sun rises, I am sandwiched between thousands circling the chariot—ahead of its two-week journey, hand pulled eight kilometres to Bungamati—reaching high to make offerings at the mobile shrine. Men sing from prayer books, women burn butter candles, and the gods seem close and content. Days of rain follow after five months of almost zero precipitation, so if the Celts were right about “thin places”—where the gap between heaven and earth narrows so the divine animates the mundane – the Kathmandu Valley must be gossamer.

Patan, also known as Lalitpur or “city of beauty”, is the oldest of the three ancient capitals of the Kathmandu Valley, the others being Kathmandu and Bhaktapur. This trio of city states was ruled for more than half a millennium by the Malla dynasty, cousin kings and cultural rivals whose ancestors fled the Muslim Conquest of India and came to power around 1200. Armed with taste and money—the valley lay at the crossroads of lucrative trade routes—the sophisticated Malla kings ushered in a golden age not dissimilar to the Italian Renaissance. The cities were separated by swathes of farmland until a decade or so ago but now, with urban sprawl, Patan reads like a suburb of Kathmandu, separated only by the Bagmati River. Culturally, though, the two places are very different. More arty, Buddhist and traditional, Patan has a gentler pace than Nepal’s frenetic capital.

I hadn’t even heard of Patan until my friend Kim Stewart launched Cashmere Luxe a few years ago, making shawls and blankets with the weavers of Nepal. Around the same time, I abandoned my career in interior design to pursue a more itinerant life as a travel writer. Kim then urged me to come to Nepal and to stay in Patan, introducing me to Camille Hanesse, who owns the accommodation agency Cosy Nepal.

Cosy forms the fulcrum to my gallivanting back and forth across the Kathmandu Valley. I stay in several historic properties from their portfolio, beginning with the super-charming Attic Studio at Yatachhen House, a Newar beauty from the 18th century with a single bed, a private terrace and Rear Window-like views over Patan’s crumbling courtyards. Another is the sumptuous Karma Duplex, with a trio of carved-timber window seats typical of Newar architecture, overlooking the temples of Swotha Square. Some of these stays last weeks, affording me the time to feel the rhythm of daily life.

A microcosm of local activity, Swotha Square might look much as it did 200 years ago if it wasn’t for the scooters, iPhones and the odd modern-nomad-filled cafe. Cross the square from Yatachen House to the local grocery store where Lalita greets you with a “Namaste” and the most beautiful smile. Head down a tiny laneway to Cafe Swotha for steaming momos—Tibetan/Nepalese dumplings fat with vegetables, chicken or buffalo—or to Samui Hasegawa for delicious Japanese. At Coffee, Tea and Me the handsome Ruby, who worked for years as a chef in Sydney, dishes up schnitzel and other hearty staples with Nepalese twists in a Berlin-underground setting, with one of the coolest playlists in Nepal. For actual coffee there’s Swotha Kiosk and Nutopia, both on the square.

Still a little confused over religion as I’m sure I see Buddhists at the Hindu chariot, I get chatting with Bikash, a vendor of tea, coffee and real-deal singing bowls at Swotha Kiosk and ask if he is Hindu or Buddhist. “I am Hindu,” he says with a smile. “But God is God—it is all the same.”

According to a popular joke, Newars are 60 per cent Hindu and 60 per cent Buddhist and it is, for me, this harmonious intermingling of faith that is the most magical aspect of Nepal. I learn from Austin, a Canadian living on Swotha Square and doing his PhD in Newar Buddhism, that Hindus will use Buddhist priests and vice versa if their own is not available. Another example is the Kumari, a girl selected from the Shakya clan of the Newari Buddhist community to serve as the ‘Living Goddess’ to the Hindu kings of Nepal. There hasn’t been a king since 2008, when Nepal dropped the monarchy, although Kathmandu, Bhaktapur and Patan still have their own Kumaris—Buddhist girls worshipped by Hindus as manifestations of divine female energy.

The harmony stretches to sexuality, too. I spend three days doing meditation and yoga with a Hindu guru at Kavya Resort & Spa in Nagarkot (more on that in a moment) and when he asked me about my family on the last day, I tell him that I am gay. Not something I usually feel the need to announce but I am curious to see his response, sure that such a connected soul could not have a problem with sexuality. I am right: with great warmth he tells me that Shiva, their most beloved Hindu deity, is bisexual. Nepal might be a traditional society but somewhere in its DNA lies the world’s greatest lesson in tolerance.

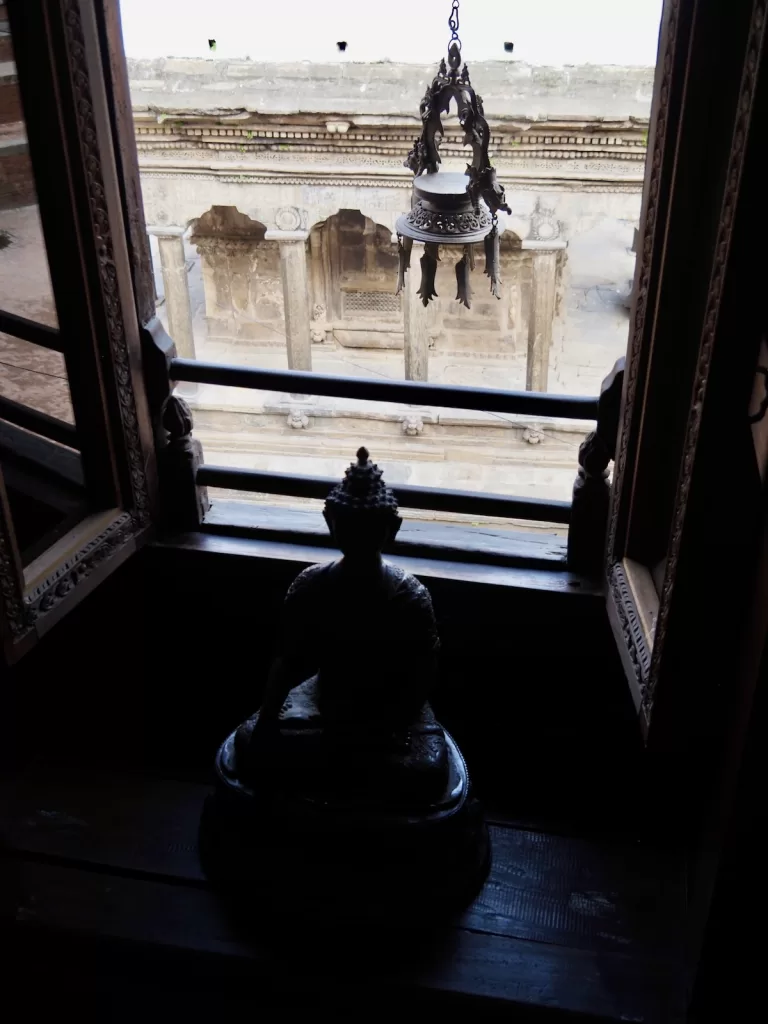

Kwa Bahal, a Buddhist monastery founded in the 12th century colloquially known as Golden Temple, is another early-morning jewel, when devotees make offerings to a child priest. The boy, always younger than 12, serves as head priest for 30 days before handing the job to another. In that time he circles the neighbourhood ringing a bell twice a day. For the rest of the time he is completely silent, although the first morning I am there he clearly has a song in his head, tapping his feet at the gateway to the shrine and singing to himself.

While Camille and her partner, Nico, are French, it is through them that I get my first taste of Nepalese hospitality: dal bhat with the Cosy crew one Friday—the rice and lentil-based national dish reputed to cure altitude sickness—and an afternoon of mahjong and ice-cold Barahsinghe beer with their local and expat friends.

Nico arrived in Patan in 2011 to set up a visual communications office after completing an internship at the United Nations in Thailand. “I didn’t know what Patan was and remember driving from the airport that first night and being pissed off that I wasn’t staying in Kathmandu,” he says. “But once I discovered the magic of Swotha Square, I was very happy to be here.”

At the time Camille was completing her degree in international affairs in Russia and came to Nepal to see Nico. “Swotha Square has always been the reason we stayed,” she says. “You have to imagine that when we arrived, it was still extremely authentic, with no tourists, nowhere to get a coffee and only local shops like a butcher and shoemaker. It was like stepping back in time and that was our fascination: here was this place that seemed totally undervalued by everyone. No one seemed to care about the beauty and harmony of the setting.”

Very early on, the couple met Jitan, owner of Yatachhen House, and after working on a handful of restoration projects together, they became partners in Cosy Nepal. “Jitan was the first guy in old Patan to have renovated in this way,” says Nico. “He took an old and very dark Newari house, opening walls and moving the kitchen from the roof to the ground floor to create more interaction around food.”

“Newars always put their kitchens on the top floor,” says Camille. “They don’t welcome foreigners, strangers or lower castes into that space, which is private and very sacred. But Jitan is an atheist, which is quite rare and special here and this impacts his way of thinking across the board.”

Celebrated artisans and town planners, the Newars were known for handsome brick buildings with intricately carved timber arcades and windows and even today, their studios and sculpture workshops line many of Patan’s laneways. The apex is Patan Durbar Square, where temples rise like pieces on an architectural chess board. A building on the square’s eastern side was once the palace of the Malla kings and is now the Patan Museum.

My interactions with Patan Durbar range from watching the square fill with thousands of women in matching red saris one afternoon during the chariot festival, to accompanying Camille as she dishes out home-cooked food to stray dogs late one night, afterwards watching boys breakdance until we are all chased away by a security guard. It isn’t until my second week, though, that I visit the museum, looking for cover during one of Rato Machindranath’s downpours. I am spellbound by the silence, as well as the architecture and collection, softly lit as if by candle and beautifully displayed against peach-coloured walls. There are fine architectural drawings, one depicting the Vambaha Chaitya, a stupa-topped shrine dating back to the 7th century. Signage is minimal and even the museum labels are chic. Armed with an entry pass that lasts the duration of my visa, I decide on my first visit that I will explore the museum slowly, communing with just one statue or to photograph just one courtyard in a particular light or, when it is raining, sitting in one of the carved window seats overlooking Patan Durbar.

The collection comprises architectural relics and religious works, such as a 9th-century image of Indra, the Hindu Zeus; an 11th-century bronze Shiva Linga, the linga representing the phallus of pleasure-loving Shiva; and a sublime 12th-century Shakyamuni Buddha seated in meditation. All have one thing in common. They were stolen.

When Nepal opened up to the world in the 1950s, the Kathmandu Valley was an open, living museum. An illicit trade in religious art followed, stripping Nepal’s gods from their shrines. The treasures on display in Patan Museum are the items that were either abandoned by thieves or intercepted before they could leave the country, making the criminal world the museum’s largest benefactor. There are also happy moments of cultural repatriation: while I am in Nepal, the Art Gallery of NSW returns an 800-year-old strut that had been stolen from a Patan temple in 1975.

There are forays into Kathmandu to visit Hanuman Dhoka and the Buddhist stupas of Swayambhu and Bouddha, spinning bronze prayer wheels with the crowds. I brunch at Le Sherpa, which not only does a mean Bloody Mary after a cocktail-fuelled night at Barc with Camille, Nico and Austin, but is home to the capital’s coolest farmer’s market each Saturday. Another day is spent wandering the hobbit-like pavilions of Taragaon Museum. Completed in 1974, the complex was designed as an artists’ hostel by Austrian architect Carl Pruscha to a concept by the Nepalese social activist, Angur Baba Joshi, that now forms Kathmandu’s coolest art gallery.

And then, after days of rain, Rato Machindranath reveals yet another miracle from the balcony of a rooftop cafe. Having washed away the thick, pre-monsoon air, the rain god shows me the Himalayas for the first time, rising up from behind the pagodas of Patan Durbar Square. I can’t believe how close they have been this whole time.

Most people do Bhaktapur as a day trip from Kathmandu, but drawn to its grand architecture and sleepy reputation, I stay for a week. Of the three ancient Malla capitals, all World Heritage sites, Bhaktapur has received the most complete restoration after the devastating 2015 earthquake, followed by Patan and then Kathmandu. Bhaktapur Durbar Square is magnificent although there are also two other beauties. Taumadhi Square has the grandeur, home to the tallest pagoda temple in Nepal, and Dattatreya Square is more intimate, the oldest of the three.

It is close to Dattatreya that I stay at Milla Guesthouse. Renovated by the Austrian architect, Götz Hagmüller, the four-room B&B takes its name from his wife, Ludmilla, an actor and stage designer. It’s simple but chic with terracotta tiles, half-painted walls in burnt orange, and brass pendant lights designed by Hagmüller. To my delight, the same posters from Patan Museum are framed and hanging on the walls.

The penny drops on the second day of my stay. I sit down with Ravi, a native of Bhaktapur, and his Polish wife Emilia, who together run Milla Guesthouse. I mention buying the same posters and that Patan Museum was one of the loveliest I’d ever seen. “My foster father Götz was the architect,” Ravi tells me. “He was commissioned by the Austrian government to oversee the renovation of the palace and its conversion to the museum.” He tells me of Kutu Math, the historic home they share with Götz and Ludmilla, and invites me for supper the following night. I meet the legendary Hagmüller and am given a tour of the math, built in the 18th century as a hostel for Hindu pilgrims and found by the architect after moving to Bhaktapur in 1979. Like Patan Museum, the line between old and new is beautifully blurred.

I return to photograph Kutu Math another day, including the striking baithak with its bay window overlooking the courtyard, and Hagmüller’s studio. On the way out, Ludmilla takes me to see a small but incredible room lined with murals telling the story of Krishna’s youth, where the holy man who ran the hostel received pilgrims. The hereditary religious elder and his family still live in the house, sharing Kutu Math with Hagmüller and his family.

The gears shift after Bhaktapur, with four days in Nagarkot at the just-opened Kavya Resort & Spa. At 2,200 metres, its tree-clad landscape is surprisingly gentle, with Kavya’s luxurious villas (rooms start at a super generous 167m2) perched like sculpture with views across deep valleys all the way to Everest. If you’re after wellness, this is the place. A wonderful in-house swami, Sri Guruji, teaches meditation and Nepalese yoga that incorporates micro movements—perfect for bodies less flexible than they once were. Kavya is also my introduction to the nature of the Himalayas, with hikes through forests and a visit to the hermit priest of a rustic mountain temple dedicated to Shiva. Kavya is about as luxurious as Nepal gets, with a vast spa, excellent service and a kitchen dishing out Pan-Asian deliciousness that will have you wanting to stay for a month.

The hiking on my non-trekking adventure gets serious in Pokhara. From The Pavilions Himalayas, a luxe farm stay with a natural-water swimming pool and farm-to-table menu, I wake up early to meet my guide, Big D, who takes me on an eight-hour hike. The first ascent is terrifying—a narrow path with a vertiginous drop to one side, made treacherous by a downpour. But the exhausting joy is unforgettable, crossing stupas and temples shrouded in clouds that open to reveal the Annapurna range. We make our way down to Phewa Lake and much needed momos at the restaurant of lovely sister property, The Pavilions Lake View.

I discover more hitherto unknown leg muscles while hiking from Tiger Mountain Pokhara Lodge. With its epic mountain views and old-world safari feel, it’s romantic as all get-out. The main lodge has a central fireplace surrounded by cane armchairs, while a large table is decorated with antique boxes and signed photos of Edmund Hillary, who inaugurated the lodge in 1998, alongside (then) Prince Charles and Princess Anne. In my room, the top floor of a two-storey rammed-earth cottage at the edge of the property, a desk piled high with vintage art books sits in front of a four-poster bed and smart-looking works on paper reminiscent of Donald Friend. There’s no coffee machine but with a butler who wakes you up at whatever time the clouds open to reveal Machhapuchhare—a sacred 7000-metre peak that has never been climbed—who needs one.

I break the drive back to Patan with a few days at the hilltop town of Bandipur, a stop on the trade route to Tibet that fell into decline when the Prithvi Highway went through in the 1970’s. The result is a sleepy Shangri La with a main, cobbled street lined in 18th- and 19th-century merchant houses, a row of which have been made over as The Old Inn. There are no frills to this eagle’s nest of a boutique hotel, although it oozes atmosphere—the otherworldly inn would make a brilliant film set—with great service, organic vegetables grown in the garden and majestic views of the Annapurna range.

My last night in Nepal is the opening of a production of Kafka’s Red Peter, staged by Ludmilla in the theatre of a Kathmandu hotel. I go with Camille; Emilia is there too while Ravi stays in Bhaktapur to look after Götz. Despite the heat, I enjoy my first taste of Kafka more than I expect, with stellar performances and the hotel staff waiting for us after the play with trays of ice-cold beer. I stand in the lobby chatting with the actors, their friends and families and these three dynamic and wonderful women, who at different times and for different reasons have made Nepal their home.

From a story originally published in Australian Financial Review Magazine.

This exploration of the magic of Nepal is dedicated to Götz Hagmuller, who died peacefully in his sleep at Kutu Math, his home in Bhaktapur, in February 2024. He was 85.