Ricardo Bofill.

The passing of the Spanish architect calls for an exploration of his use of pattern and form to enrich the lived environment.

Over the years, there have been a handful of outlier architects whose edificial conjurings appear as plucked from the prehistoric or ancient worlds as they might have been from a far-off planet in Star Wars. The Flintstone-like homes designed by Jacques Couelle on the Cote d’Azur in the 1950’s are one example. The cave-to-spaceship designs of his Californian contemporary, John Lautner, are another. The fantastical work of Catalan architect Ricardo Bofill Leví is yet another. What makes Bofill so compelling, alongside the work itself, is that unlike his peers who worked and thrived in free and culturally flourishing environments, he did so from under the repression of Spain’s Franco dictatorship.

The eclectic oeuvre of Bofill, who died in January at the age of 82, brought new sui generis meaning to postmodernism. “When I was 35, I was the most fashionable architect in the world,” he said. “But I was always an outsider, never fitting in with architectural culture.”

Underpinning his work were visions of utopia, alongside nods to literature and philosophy, as evidenced in grand and expressive residential projects such as El Castillo de Kafka (1964-68), Xanadu (1967-71) and Walden-7 (1975). The cubic volumes of Ibizan villages and North African kasbahs permeating the design of Kafka and Walden-7 exemplify his passion for vernacular architecture, discovered while travelling as a youth. “I learned more in the middle of the Sahara, among nothing but dunes and sand, than in a French palace,” he said.

Comprising 446 apartments, Walden-7 appears like a terracotta beehive on the outskirts of Barcelona, as singular and thought provoking today as it must have been in the 1970’s. It’s irregular rhythms allow for public spaces connected by bridges and balconies that make for incredible vistas and enclosures, there to enhance the inhabitant’s quality of life in a non-repetitive way. Internal layouts, meanwhile, are based on modules. “It was about liberation from the traditional family structure,” said Bofill. “Now it’s become a bit more bourgeois.”

Ricardo Bofill Leví was born in Barcelona in 1939, during the dark and early days of the Franco regime. His cultivated family fostered his love of architecture: father Emilio Bofill was himself an architect and builder while his Jewish-Italian mother, Maria Leví, championed Catalan literature and culture.

He began his architectural studies at the Universitat de Barcelona in 1957 – tumultuous times for anyone not aligned with Franco’s right-wing dictatorship. Supporting the Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia, outlawed at the time, Bofill was arrested during a student demonstration the following year. Expelled from the university – and Spain – he completed his studies at the École des Beaux-Arts in Geneva, Switzerland.

After graduation, he returned to Barcelona and established Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura, in 1963. The studio’s output, however, was not the stuff of standard architectural practices. Thomas Weaver, a lecturer at the AA School of Architecture in London, described Bofill’s creation as “groundbreaking projects and buildings produced by an exuberant Spanish office, whose staff consisted of a cast of young designers together with a resident poet and a resident philosopher.”

La Muralla Roja (1968-73), which translates as ‘The Red Wall’, is arguably Bofill’s most ebullient work – a fantasy, technicolour fortress perched upon a cliff overlooking the Mediterranean, near Alicante. It recalls Escher’s drawings of impossible constructions and while it looks nothing like Walden-7, the structure also takes inspiration from the staggered shapes of North African kasbahs. An array of stairs and corridors offer multiple views and perspectives where the play of colour and light is everything. The variously shaded red exterior contrasts with the surrounding land- and sea-scape, while the pale blue, indigo and violet of the patios and stairs connect to the sky. Several of La Muralla Roja’s one- and two-bedroom apartments are available to rent via Booking.com.

Across the border at La Espaces d’Abraxes (1978-82), a vast social housing project east of Paris, Bofill applied the golden rules of the French Renaissance in precast concrete as if Stalin and Louis XIV got together and designed a socialist Versailles. His words might have been those of the Sun King himself: “I wanted, once and for all, to create a space powerful enough to make normal people who know nothing about architecture realise that architecture exists.” Ironically this grisaille utopia formed the backdrop to the dystopian cult film, Brazil and more recently an instalment of The Hunger Games. La Muralla Roja, meanwhile, inspired the sets of Squid Game, with a selection of apartments within the kaleidoscopic complex available for holiday rental.

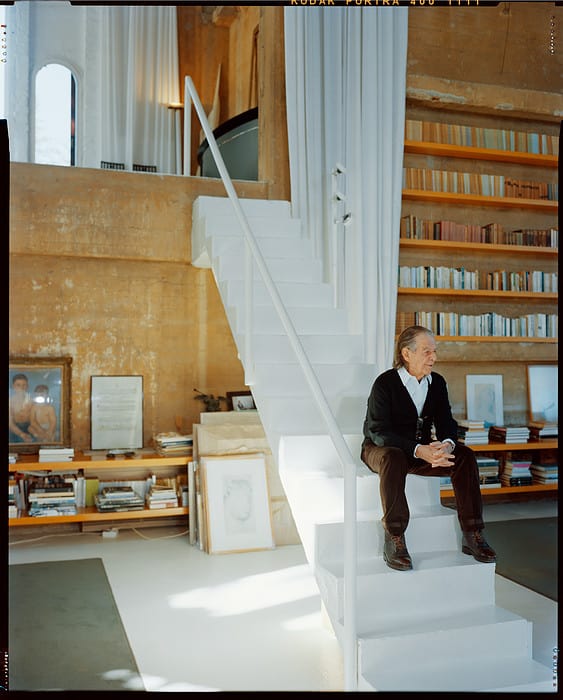

La Fabrica is the home and base of operations Bofill fashioned from the shell of an abandoned Barcelona cement factory in 1975. The sole use of colour is the green of the site’s Babylonian garden while inside, soaring, cathedral-like spaces are punctuated only with spartan arrangements of furniture and three-storey high white curtains. From this dream-like, magical setting – an Arcadian ruin in a futuristic Piranesi – sons Ricardo Emilio and Pablo will continue their father’s architecture of good intentions.

From a story originally published in Vogue Living.